By Anna Wyckoff | August 29, 2023

Get To Know

Our Illustrator Members

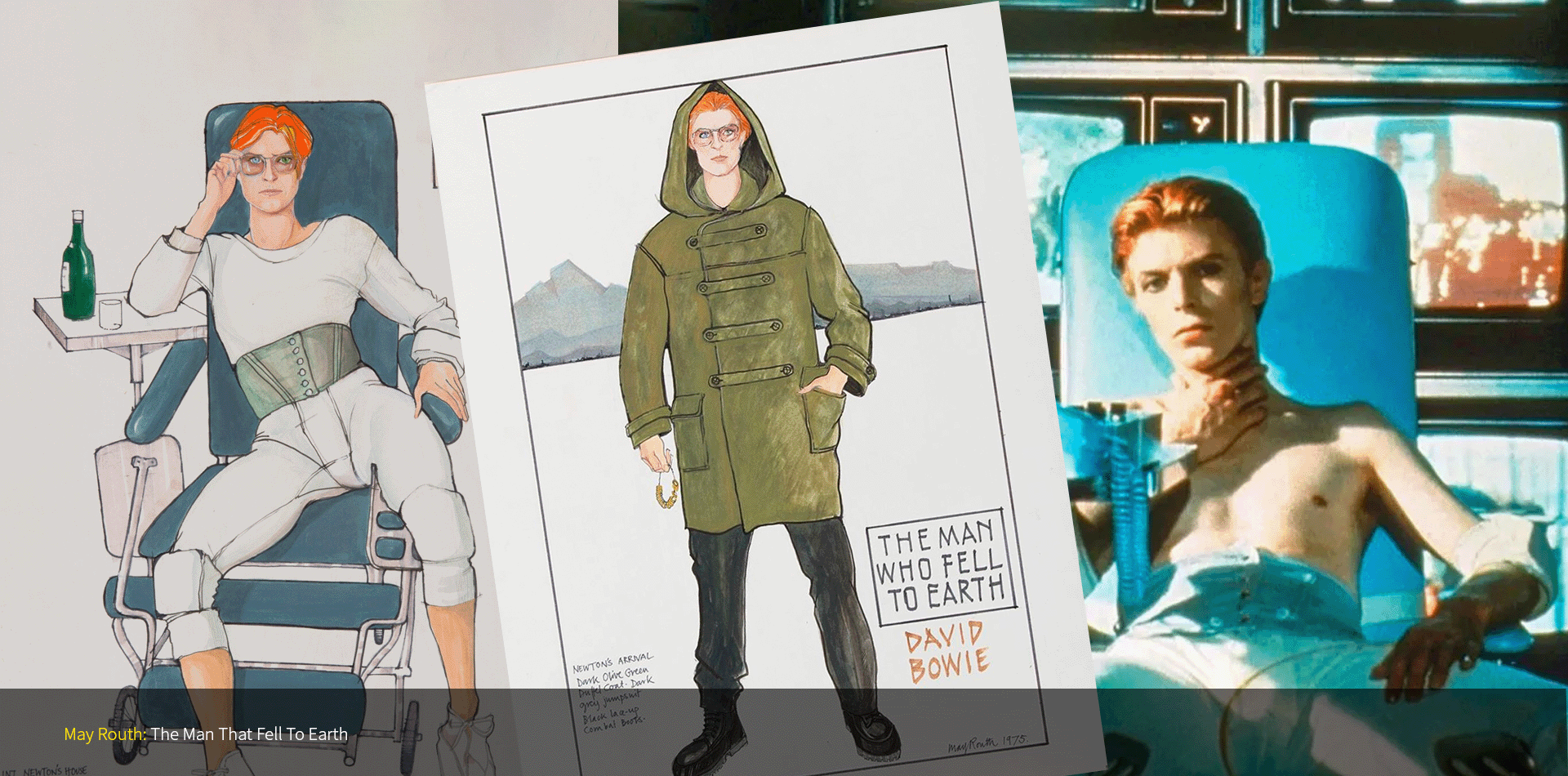

This page showcases over 50 costume illustrations for film and television, created by our talented illustrators and concept artists.

Archives

“Star Wars Vs. Star Trek” October 1, 2020

“Designers Are a Girl’s Best Friend” January 18, 2021

“Minari: Living The Korean American Dream” January 26, 2021

“Magic In Minutes: SNL’s Eric Justian & Tom Broecker” January 31, 2021

“Star Power” March 9, 2021

“Fashion as Fiction” June 28, 2021